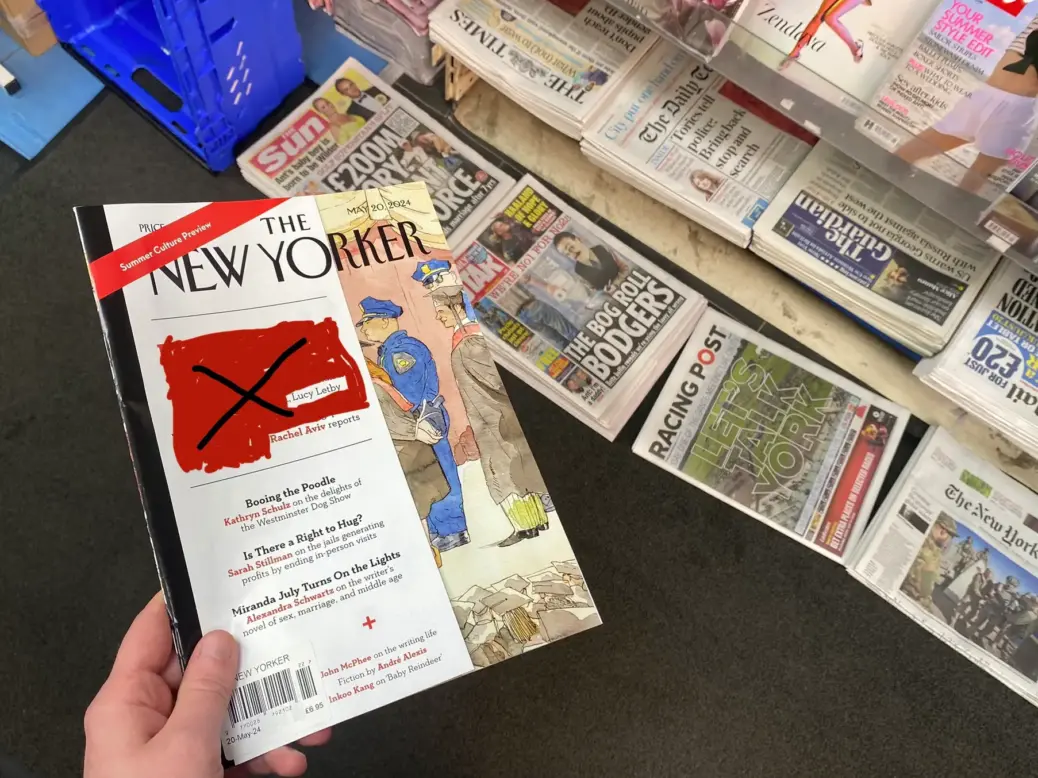

Last year, UK readers found themselves unable to read an online article published by US magazine The New Yorker about the convicted murderer Lucy Letby.

But this was not a straightforward case of online censorship – it was due to UK laws that prohibit or restrict the publication of potentially prejudicial material.

Contempt of court exists to protect all court and tribunal proceedings from interference, to safeguard the fairness and integrity of proceedings, and to ensure that orders of the court are obeyed. It comes in many forms, both statutory and under common law. Part of that law is based around “contempt by publication”.

In the UK, for the purposes of reporting, a criminal case becomes “active” when someone is arrested, or a summons or warrant is issued. It remains this way until a defendant is sentenced or acquitted.

As journalism has increasingly moved online and become more international, it has become harder to strike the balance between freedom of expression (as established in Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights) and the right to a fair trial (Article 6).

Contempt laws cover a wide variety of conduct, including misbehaving in the courtroom (“scandalising the court”), refusing to answer a court’s questions if called as a witness, and deliberately breaching a court order – but they also cover situations where journalists, bloggers or members of the public publish material that might risk prejudicing a trial.

Some obvious examples would be publishing a defendant’s previous convictions or implying that someone is guilty before they have been tried.

UK law on “contempt by publication” is primarily set out in the Contempt of Court Act 1981. This enacts what is known as the “strict liability” rule, which applies once criminal cases are active. At this point, any publication that creates “a substantial risk” that the course of justice will be “seriously prejudiced” will be in contempt. This “substantial risk” is assessed on a case-by-case basis.

In the Letby case, the New Yorker article was geo-blocked in the UK, although it could still be read in the print magazine.

Neonatal nurse Letby had been found guilty at a trial in 2023 of murdering seven babies and attempting to kill six others. She had been sentenced to a whole-life prison sentence.

At the time of the article’s publication (May 2024), Letby was awaiting a retrial on one charge of attempted murder, scheduled for the following month. The judge put a series of reporting restrictions in place around what could be said about the original trial. There was concern that the New Yorker piece might breach those restrictions and prejudice the jury hearing the retrial.

Concerns about the impact of reporting on juries is a key part of contempt by publication. Judges are expected to be able to rise above what they read in the press – in 1960, a judge put it as such: “A judge is in a different position to a juryman. Though in no sense a superhuman, he has by his training no difficulty in putting out of his mind matters which are not evidence in the case. Jurors, on the other hand, are more likely to be influenced by what they read in the media and elsewhere.”

When the 1981 act was passed, there was no 24-hour rolling global news, internet, social media or blogging. Publication was generally by printed articles in UK-based newspapers and news reports on television or radio.

In 2007, Richard Danbury, a former investigative journalist and now a senior journalism lecturer at City St George’s, University of London, wrote a Reuters Institute report on this very topic, and described “the danger posed by the rise of the internet to the doctrine of contempt”. “It risks becoming unenforceable,” he wrote.

In 2011, in what was described as a landmark ruling for internet publishing, daily newspapers The Sun and the Daily Mail were found guilty of contempt over the online publication of a picture of the defendant in a murder trial posing with a gun.

Despite lawyers for both newspapers arguing that the risk of prejudice was “insubstantial” because the photo was quickly removed and jurors had been ordered not to conduct online research, the court concluded that the photograph created “a substantial risk of prejudicing any juror who saw [it]”, adding: “Once information is published on the internet, it is difficult if not impossible completely to remove it.”

1981 legal framework ‘increasingly flimsy and ineffective’ in 2025

Fast forward to 2025, and a legal framework that was intended to protect juries from prejudicial publication looks increasingly flimsy and ineffective when viewed against a backdrop of smartphones, echo chambers, citizen journalism and the dissemination of lies and disinformation by the rich and powerful on social media.

In recent years, in an attempt to manage the risk of contempt by publication, the UK attorney general’s office has taken to issuing what it calls “media advisory notices” in high-profile cases, but these often just restate general principles and sometimes actually get the law wrong.

Unfortunately, we have ended up with a two-tier system in which the mainstream UK media (which are generally respectful of the law) is often seriously restricted in what it can publish while people on the fringes of the wild web are spreading the sort of (mis)information that the law is meant to be restricting.

This is often published to a much wider – and more gullible – audience. As former attorney general Dominic Grieve commented in 2011, “the inhabitants of the internet often feel themselves to be unconstrained by the laws of the land”.

Under the law, a publisher is liable for material legitimately posted online before legal proceedings become active, and which is then considered to be prejudicial once a case is active.

In practice, most UK publishers are careful not to link to old news reports within new reports of live cases about the same defendant, so the chances of a juror seeing possible prejudicial material are pretty slim. Jurors in the UK also now get very specific instructions from trial judges not to do their own online research, and in 2015 a criminal offence was introduced for jurors who do so.

However, this still effectively imposes an impossible burden on the media to monitor online archives to check whether they relate to newly-active legal proceedings. This task has become even harder since 2013, when the police decided to stop naming people who had been arrested, and instead name them only when they were charged.

A lot of these issues came to a head last summer after the Southport stabbings, in which three children were killed at a dance class in the north-west of England. Concerns were raised about the lack of official information available to counter misinformation spreading on social media about the attacks, and that misinformation was blamed for riots and violent protests across the country.

In the hours immediately after the stabbings, only a short statement was issued by police to say that “armed police have detained a male and seized a knife”. This lack of public information appears to have been the result of a rather problematic combination of concern over contempt by publication rules, court-made privacy law around not naming suspects before charge, and statutory reporting restrictions around naming under-18s.

It is also hard to enforce contempt laws against articles that are uploaded outside England and Wales. As we know from the debate over online safety, domestic courts have struggled with extra-territorial jurisdiction when it comes to the internet.

Need for ‘public interest’ defence for alleged contempt

So, what is to be done? In the digital arena, the protective approach towards court reporting in the UK seems to set too high a threshold, is imprecise and, operationally, ends up being over restrictive in some ways and ineffective in others.

Our laws do not give sufficient credit to the robustness of the jury process. Juries must be trusted to reach verdicts on the evidence placed in front of them during the trial.

There is a need for a specific “public interest” defence where contempt by publication is alleged, which would allow for questions of proportionality and balance to be asked.

There is also an argument to be made for moving the point at which criminal proceedings are considered “active” away from the moment of arrest and forward to the point of charge. This would be more consistent with the criminal justice process, as a charge is the moment when it is definite that there will be a trial.

This is not to say that the UK should move towards a US-style legal system, where freedom to publish can sometimes seem to take precedence over fair trial considerations.

In July 2024, the Law Commission – a UK statutory independent body – launched a wide-ranging consultation on contempt of court with a view to reform.

The consultation initially closed in November, but last month a brief supplementary consultation paper was published (which closed on 31 March) as a result of issues arising out of the Southport attacks last year.

It warned of the growing conflict between contempt of court laws and public safety: “It has been suggested that the disorder was an indirect result of contempt of court laws: in constraining what information public authorities could disclose in relation to the defendant, contempt law helped to create an information vacuum in which misinformation, disinformation and counter-narratives could spread unchecked.”

The Law Commission is expected to publish its initial report on liability for contempt (including contempt by publication, which will also address the issues raised in the Southport attacks) later this year.

No one wants trial by the media, but it is vital that in the age of the internet the courts strike the right balance between ensuring a fair trial and freedom of expression.

This article was first published by Index on Censorship on 10 April 2025. It appeared in Volume 54, Issue 1 of Index on Censorship’s print magazine, titled: The forgotten patients: Lost voices in the global healthcare system. Read more about the issue here.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog